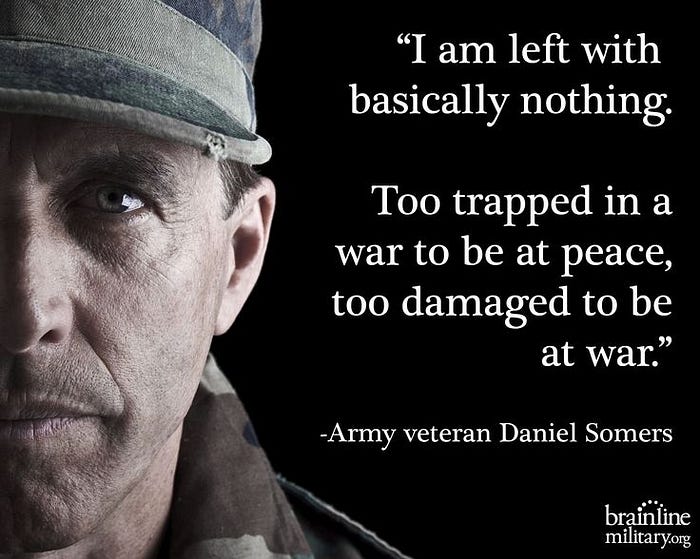

The Thousand-Yard Stare

Taking a frightening look at combat trauma over the years

Soldiers call it the thousand-yard stare — the tell-tale sign that one’s senses have become so overloaded by prolonged fear and trauma that the nervous system can’t process any more. They are no longer looking at you in the here and now. They’re looking through you into the distance, toward something far beyond — be it heaven or hell. Or maybe a little bit of both.

Soldiers call it the thousand-yard stare — the tell-tale sign that one’s senses have become so overloaded by prolonged fear and trauma that the nervous system can’t process any more. They are no longer looking at you in the here and now. They’re looking through you into the distance, toward something far beyond — be it heaven or hell. Or maybe a little bit of both.

Over the years it’s gone by many names and medical science has basically been playing catch-up to the furious advance of warfare. It’s been called shell shock, combat stress reaction, battle fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But whatever the clinical label, the circumstances surrounding it remain very much the same.

British photographer Don McCullin captured it perfectly in 1968 with his portrait of an unknown American Marine during the battle for the city of Hue during the Vietnam War. While on assignment in Hue, McCullin was drawn to a Marine sitting there motionless while still holding onto his weapon. McCullin approached him carefully and instinctively brought his camera up to take a series of five snapshots. In that time his subject’s stony expression never changed; he didn’t so much as blink once.1

Look closer into the man’s eyes. He’s staring back at the camera. Almost, but not quite. His expression, such as it is, is cold and detached, practically numb. He’s seen and heard and felt too much on this day and at some point, his conscious brain, in order to save itself, started shutting down. What’s left is the stare.

Historically this is nothing new. Greek historian Herodotus told of an Athenian warrior named Epizelus suddenly going blind during the battle of Marathon in the year 440 B.C. He did so after seeing his friend and comrade killed in combat. His blindness had nothing to do with physical injury and yet it lasted for years before he recovered. [2]

The term shell shock was first coined in 1915 by British Captain Charles Myers of the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War One. It was tasked to Myers to document and study the cases of soldiers from the front who were suffering from a range of peculiar but severe symptoms, including uncontrollable body tremors, stammering, sensory numbness, and impaired eyesight.

He came up with the theory that the endless barrage of shelling that soldiers faced day in and day out in the trenches of western Europe was causing dangerous physical concussions to their nervous systems, hence the name shell shock.

However, the following year there came a loophole to that theory when it was noted that many men who were being classified as victims of shell shock were never once near any exploding artillery shells. By the end of that war, there were over 80,000 recorded cases of shell shock in the British army alone.[3] Obviously, there was a serious need to learn more about these bloodless afflictions.

World War Two brought even more carnage and destruction to millions of soldiers and civilians around the world. Battle fatigue became the new diagnosis for those who suffered mental breakdowns after experiencing trauma on the battlefield.

Twenty-one year-old Marine private Eugene Sledge knew what it felt like being caught in the middle of battle in the Pacific during World War Two. In his autobiographical book With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa he described it like this:

“I was terrified by the big shells arching down all around us. One was bound to fall directly into my hole. I thought it was as though I was out there on the battlefield all by myself, utterly forlorn and helpless…. My teeth ground against each other, my heart pounded, my mouth dried, my eyes narrowed, sweat poured over me, my breath came in short irregular gasps, and I was afraid to swallow lest I choke.”

Experiences like that lasting for hours and days on end took its toll on many a strong man throughout the war.

After the war, doctors struggling to better understand the psychological side of combat came to the conclusion that the long deployment of soldiers in their tour of duty — often lasting several years — was a major factor in causing battle fatigue. Then why was it that the vast majority of men who served long deployments in World War Two did not suffer from battle fatigue? Again there were no easy answers.

Following the Vietnam War, medical and mental health experts started delving deeper into the issues of stress in combat. What they came up with was post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Severe anxiety and depression, violent memory flashbacks, sustained drug abuse, and high rates of suicide were identified as leading symptoms.

In Vietnam, the average age of an American combat soldier was only nineteen. A study mandated by the U.S. Congress in 1983 surveyed Vietnam veterans and reported that 15% of male and 9% of female veterans were found to still have symptoms of PTSD nearly a decade after the war was over. [4]

Even as gains were being made with regard to awareness, medicinal prescription treatment, and psychological counseling, the advance of years wasn’t bringing about a lessening of the problem. According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 12 out of every 100 Gulf War Veterans (or 12%) were or are diagnosed with PTSD in a given year. [5]

Also, it should be noted, the thousand-yard stare is not unique to soldiers in battle. Anyone experiencing significant trauma from incidences like violent attack, natural disaster, constant danger or phenomenal loss may begin to manifest acute stress disorder or PTSD.

Doubtless, there will be more armed conflict in this world, and with it there will be more honorable men and women caught in terrifying situations not of their making. In those moments they will sink deeper into their own mind, some never to fully return. That will never change.

1 https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190212-don-mccullin-the-photos-we-cant-look-away-from

2 https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/history-of-ptsd-and-shell-shock

3 ibid

4 https://www.verywellmind.com/ptsd-from-the-vietnam-war-2797449

5 https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp